Contents of the 1920 volume of Ladies’ Home Journal

by Jasmine Relovsky, Biology Major, Class of 2028, Fairleigh Dickinson University

Exploring historical health media can reveal a lot about how people viewed medicine, wellness, and their own bodies in different eras. The Ladies’ Home Journal was one of the most widely read magazines in the United States during the early 20th century, influencing how Americans thought about domestic life, health, and moral values. Examining Volume 37 from 1920 shows the kinds of messages women were receiving about their health, both through expert columns and advertisements. When compared to modern wellness trends on social media, the similarities are striking, especially in how health is commercialized and gendered. This overview highlights key trends in how medicine and wellness were discussed in the magazine and compares those historical patterns to current health trends on social media. Despite the centurywide gap, there are some surprising similarities. This includes how health is marketed, how women are still the main targets of wellness messaging, and how medical advice often gets mixed with moral or beauty standards.

Going through the 1920 volume of Ladies’ Home Journal revealed several recurring themes in how health and wellness were seen during that time period. Much of the health advice was often linked to a woman’s role as a homemaker. Cleanliness and hygiene were heavily emphasized, with articles promoting practices like regular cleaning, proper ventilation, and the value of fresh air as ways to prevent illness. The overall message was that health was a personal responsibility, especially for women, who were portrayed as the caretakers of both their family’s physical well-being and moral standards.

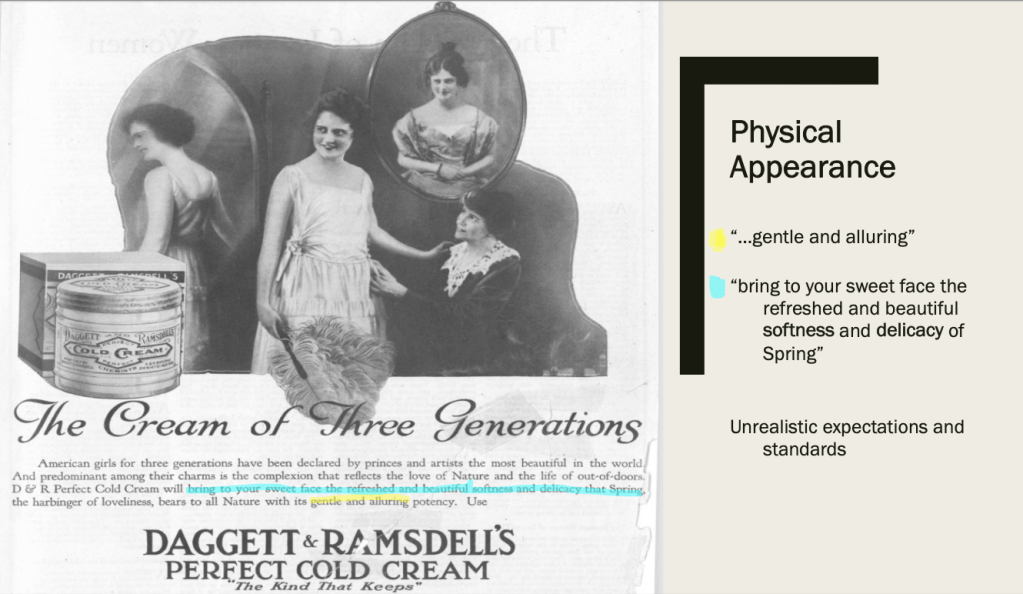

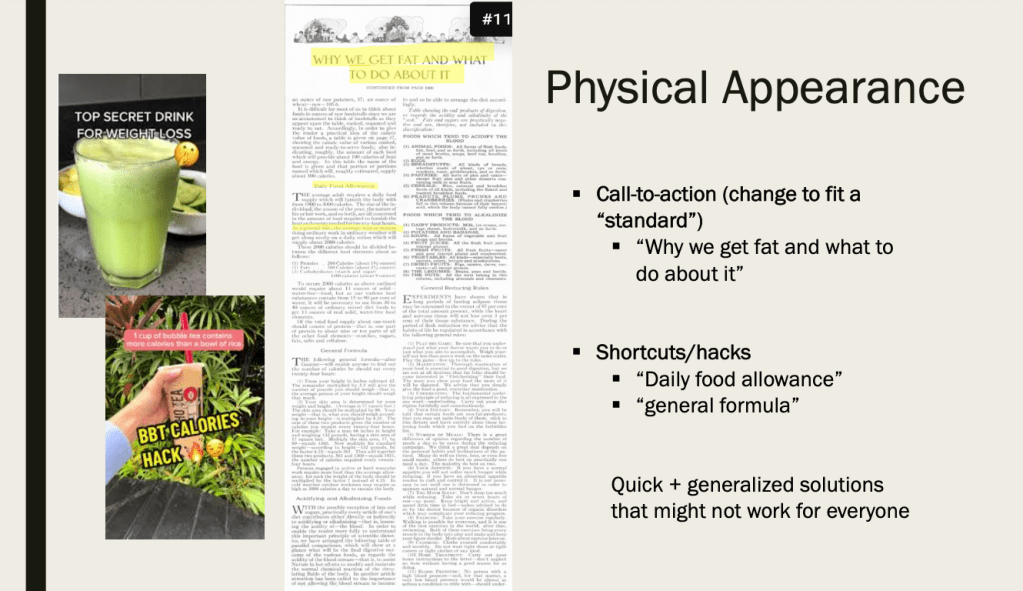

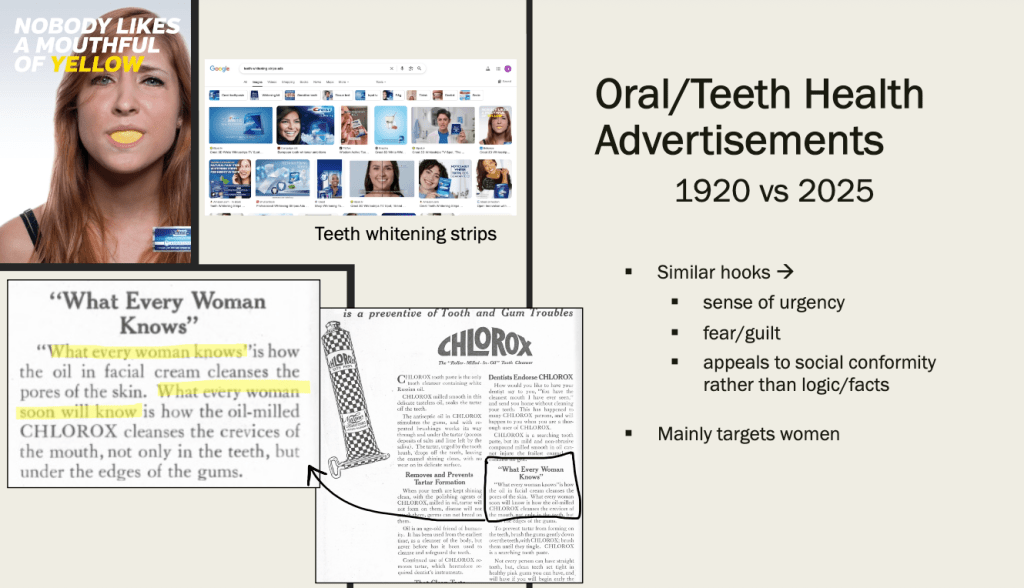

There was also significant emphasis on physical appearance, with advice on maintaining youthfulness, proper posture, and slimness, topics still relevant in modern wellness discourse. At the same time, a large portion of the health content came in the form of advertisements, promoting proprietary medicines, “tonics,” and beauty products with questionable medical value. For example, the advertisement for “Daggett & Ramsdell’s Perfect Cold Cream” (page 63) suggested that using the product would not only improve skin appearance but also enhance a woman’s overall health and attractiveness, reinforcing the idea that beauty was an essential part of being well.

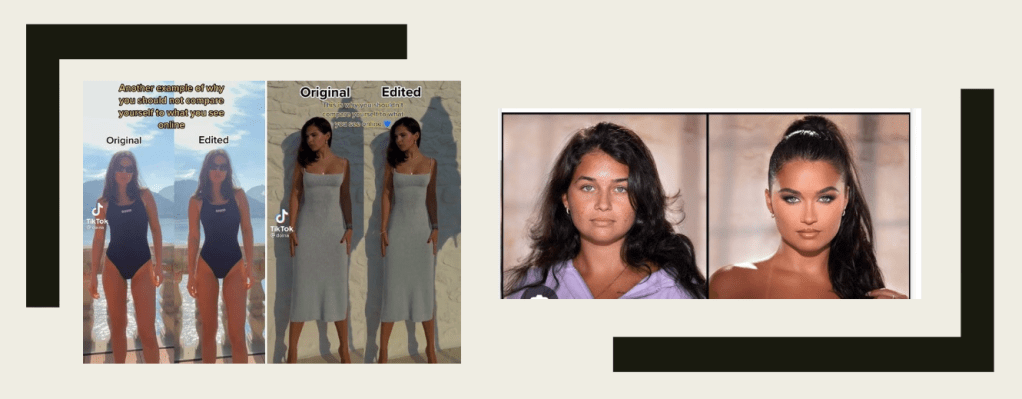

This is very similar to current wellness trends seen on social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, where influencers often promote beauty products, skincare routines, and self-care rituals as essential to both physical health and emotional well-being. Much like the Ladies’ Home Journal advertisements, today’s social media influencers emphasize the idea that looking good equates to feeling good, and that self-care is a necessary part of living a healthy life. These influencers, often with no medical qualifications/backgrounds, market products that promise emotional and physical benefits, blending beauty and health in ways that mirror the promises made in 1920s advertisements.

One specific column from this volume offered health advice from Dr. Harvey Wiley, a chemist and early advocate of food safety. Dr. Wiley’s column gave readers tips on nutrition, digestive health, and raising children in a hygienic environment. His advice, while rooted in the progressive scientific thinking of the time, was often moralistic. For example, he warned mothers against “spoiling” children with certain foods and emphasized moderation as a key to long life. His tone was authoritative, and the information was presented as practical, trustworthy science.

One ad promoted a laxative that promised to “brighten your mood” and restore energy. Such ads often blurred the line between physical and emotional well-being, suggesting that a single product could restore one’s overall quality of life. These examples illustrate the tension between trusted medical authorities and profit-driven health messaging, a tension that remains highly relevant in our current media landscape. One strong similarity is the continued gendering of wellness messaging. Just as women in 1920 were targeted with products to manage stress, regulate their periods, or slim their figures, today’s women are often the primary audience for wellness content, though the tone has shifted to emphasize empowerment and “self-care.” Both eras, however, place the burden of wellness squarely on the individual, particularly women.

In conclusion, examining the 1920 volume of Ladies’ Home Journal alongside today’s wellness trends reveals both the evolution and persistence of certain cultural patterns in how health, wellness, and beauty are marketed, especially to women. While the mediums have changed, the core messages remain the same: health is a personal responsibility often tied to physical appearance, moral standards, and the consumption of health products. Whether through informative articles or modern influencer-sponsored posts, the theme remains relatively consistent. Despite the century between them, the tension between medical authority and profit-driven health messaging, as well as the gendered nature of wellness advice, continues to shape how society perceives health. By reflecting on these historical and contemporary trends, we gain insight into the influence of media on our collective understanding of health and wellness.